This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

CMU Trends In Ten Live Music Library

CMU Trends In Ten: The Anti-Touting Campaign

By Chris Cooke | Last Updated: April 2020

This is a ten step guide to the growth of the secondary ticketing market and efforts to regulate the resale of tickets for profit by touts online.

01. Ticket touting boomed as the ticket market at large moved online

Ticket touting – or scalping as it’s known in some countries – is hardly a new phenomenon. There have long been unofficial sellers who, having acquired tickets for in-demand shows, then seek to sell them on at a marked-up price. Some of those unofficial sellers would call themselves brokers and resell tickets through a formal business. Others embraced the term tout or scalper and would buy and sell tickets near a venue on the night of a show.

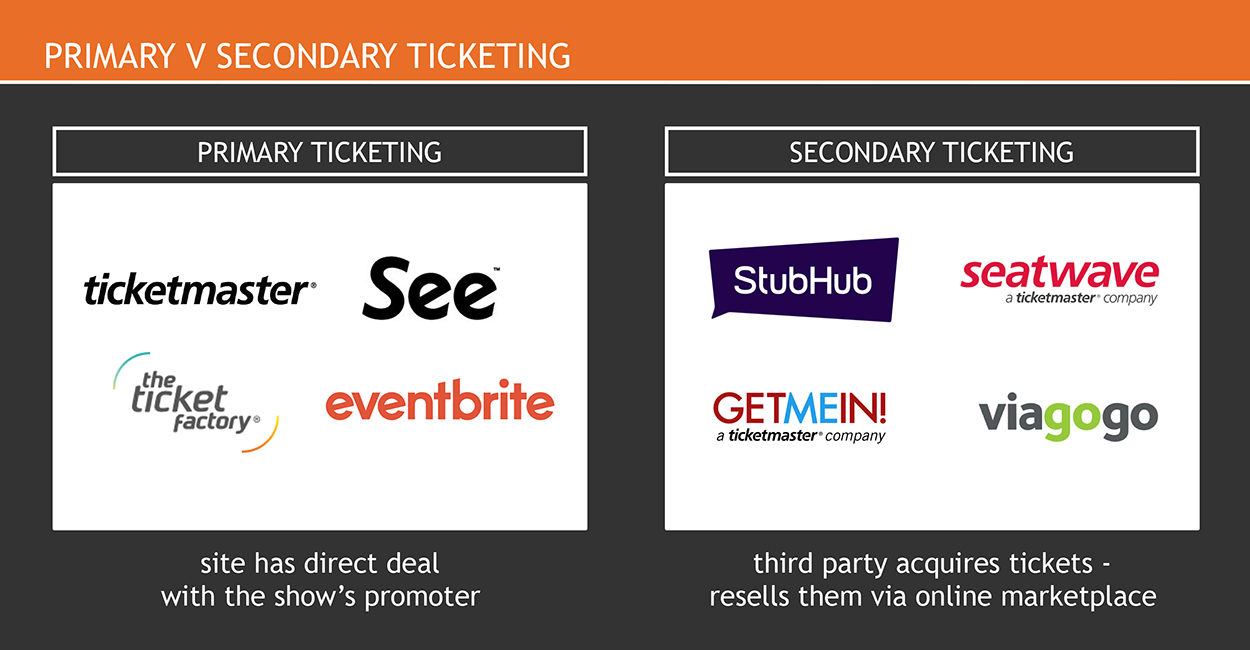

But the reach and scale of these unofficial sellers boomed as the ticketing business at large slowly shifted online in the late 1990s and early 2000s. As official ticket sellers – or primary ticket agents – started to launch websites and increasingly sell their tickets through online channels, the touts also embraced the web.

This was particularly true once auction sites like eBay started to gain momentum. These sites made it easy for anyone to sell products online without having to go to the effort of setting up their own website and online payment systems. They also provided a ready-made marketplace.

As touts started to post the tickets they were selling onto eBay-type sites, it became clear there was an increasingly significant number of music fans looking to buy. As a result, entrepreneurs saw an opportunity to develop resale sites specifically focused on tickets. These could be set up with live events and ticketing specifically in mind and therefore work in much the same way as the websites the primary ticket agents had launched.

And so what became known as the secondary ticketing market started to emerge, centred on the bespoke ticket resale platforms that were launched in the 2000s. As these new sites took the ticket touting business away from eBay, it acquired one of the biggest specialist resale platforms, StubHub, to ensure it stayed in the secondary ticketing business.

02. Concerns were quickly raised, but little happened to curtail the growth

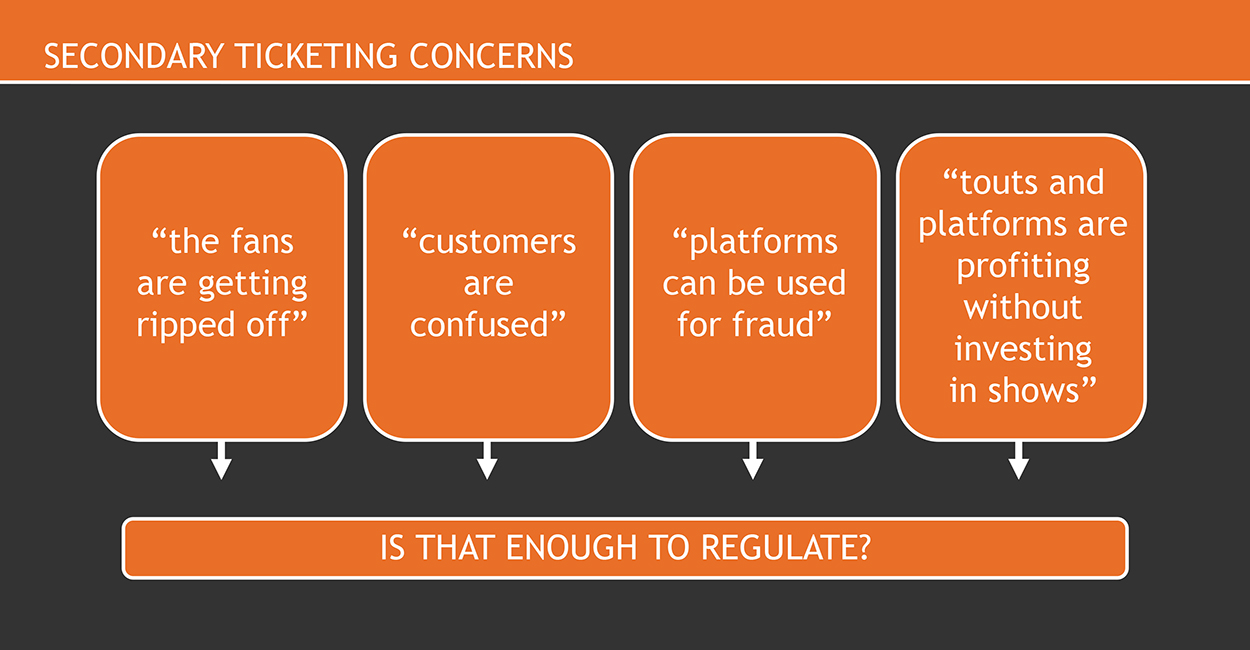

As this new secondary ticketing market began to boom in the mid-2000s various concerns were expressed by consumer rights groups and the music community.

Concern number one was that the fans were getting ripped off. As the touts got better access to the market, they tended to buy more tickets. Which meant that an increasing number of tickets for in-demand events were being bought up by the touts as soon as they went on sale. Which in turn meant an increasing number of fans were having to pay a premium to get into shows, even when they bought their tickets early on.

Concern number two was that consumers were getting confused. If you bought a ticket from a tout in the street outside a venue, you knew you were buying from an unofficial source. But online, primary and secondary sellers sat side-by-side. All the more so as the bespoke ticket resale sites launched and did everything they could to look like the websites of the primary ticket agents. This meant customers might buy at hiked up prices even when face-value tickets were still available on primary sites.

Concern number three was that the secondary ticketing marketplaces could be exploited by fraudsters who didn’t actually have the tickets they were selling. Most of the ticket resale sites sought to tackle this concern by offering a money-back guarantee if it turned out a non-existent or fake ticket had been sold on its platform. Although if a customer only finds out that a ticket is fake when they get to the venue, that’s still a major inconvenience.

Concern number four was that the touts and the platforms they used to sell their tickets – which charged sizeable commissions – were getting increasingly rich off shows they didn’t invest in. While that had always been true to an extent, the amount of money being generated by the touts was growing rapidly, plus – once online – the business of ticket touting was much easier for everyone in the industry to see.

As consumer rights groups and the music community started to raise concerns about the secondary ticketing market, politicians also started to take an interest. However, in most countries throughout the 2000s politicians tended to call on the music industry to deal with the problem of secondary ticketing, making it pretty clear that they weren’t yet in any mood to regulate the touts (France being the early exception in this domain).

03. There were supporters of the secondary market – and the music industry got involved

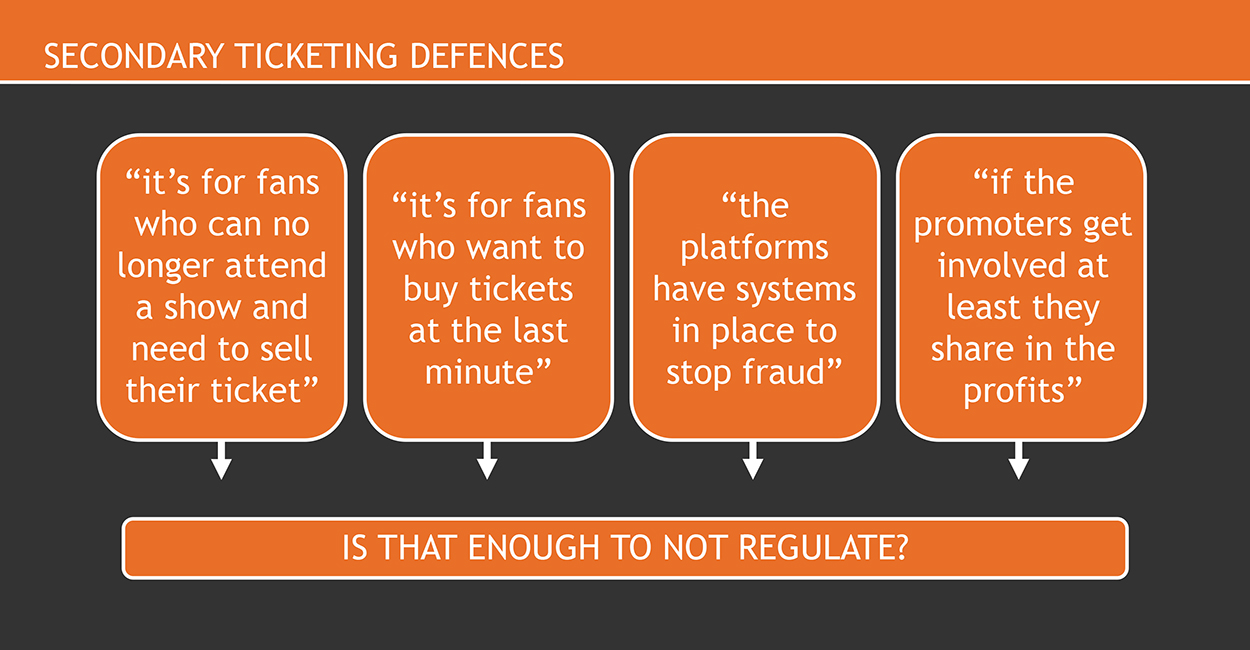

It’s worth noting that there were also vocal defenders of the secondary market during this period. And some in the music industry decided to embrace the new resale business as well.

Some in the industry saw secondary ticketing as an opportunity. Others got involved more reluctantly. Once it became clear politicians were unlikely to regulate, they decided to adopt an “if you can’t beat them join them” strategy.

As a result, some promoters started to put tickets to their own shows on the resale sites, either directly or by forming an alliance with an established tout. And some promoters and venues became official partners of the resale sites, approving the touting of their tickets on one specific partner platform in return for an upfront fee or a cut of the resale commission.

Meanwhile primary ticketing company Ticketmaster – which would later become part of the Live Nation, the biggest live music company in the world – also moved into the secondary market, mainly by acquiring some of those start-up ticket resale platforms.

04. A key question became: “what is a ticket?”

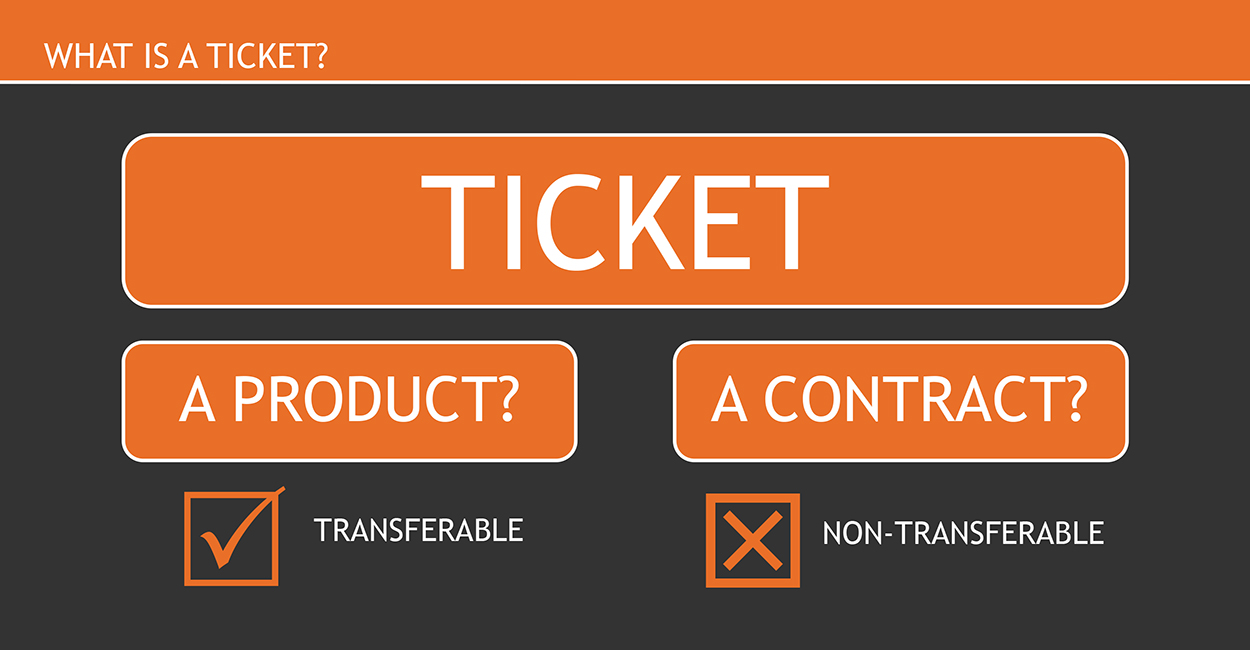

Defenders of touting at this time often argued that if someone bought a ticket they should be allowed to sell it on for profit like any other product you might buy and then resell. Although there was a strong comeback to that argument.

Many critics of touting countered that a ticket isn’t actually a product at all. Instead it is a contract between the promoter of a show and the person who buys the ticket. In that contract the promoter agrees to allow the ticket-holder to have access to a certain space at a certain time to watch a certain performance, in return for payment and other commitments as set out in the contract.

A common term in that contract is that the ticket is non-transferable. So if the ticket-holder then transfers the ticket to another person, the contract becomes void, and the promoter is no longer obliged to allow the new ticket-holder into the show.

This provided a possible solution for those in the live sector who opposed online touting: they could start to cancel touted tickets. Though this posed two challenges.

First, most resale platforms allowed touts – even industrial-level touts – to sell pretty much anonymously, and without stating the specific seat or reference number attached to a ticket. Making it difficult for promoters to identify which tickets had been resold.

Second, as the promoter doesn’t know who bought the touted ticket, they can’t let them know about any cancellation until they arrive at the venue. And given the secondary sites often looked like the primary sites, many people with touted tickets wouldn’t necessarily know they’d bought their ticket from an unofficial seller. This creates a significant communication challenge for the promoter and the venue.

Those challenges could be overcome to an extent if secondary ticketing sites were forced to provide more information about a resold ticket online, and to more clearly state to the consumer that they were not buying a ticket from an official seller and that, therefore, there was a risk their ticket could be cancelled by the promoter.

05. The Consumer Rights Act and resulting Waterson Report changed things in the UK

The UK’s new coalition government that took power in 2010 seemed even less likely to support regulation of online touting than the Labour governments that had preceded it, not least because one minister rising his way up the ranks, Sajid Javid, had once described ticket touts as “classic entrepreneurs”. However, in Parliament there were an increasing number of MPs concerned about the consumer rights implications of secondary ticketing.

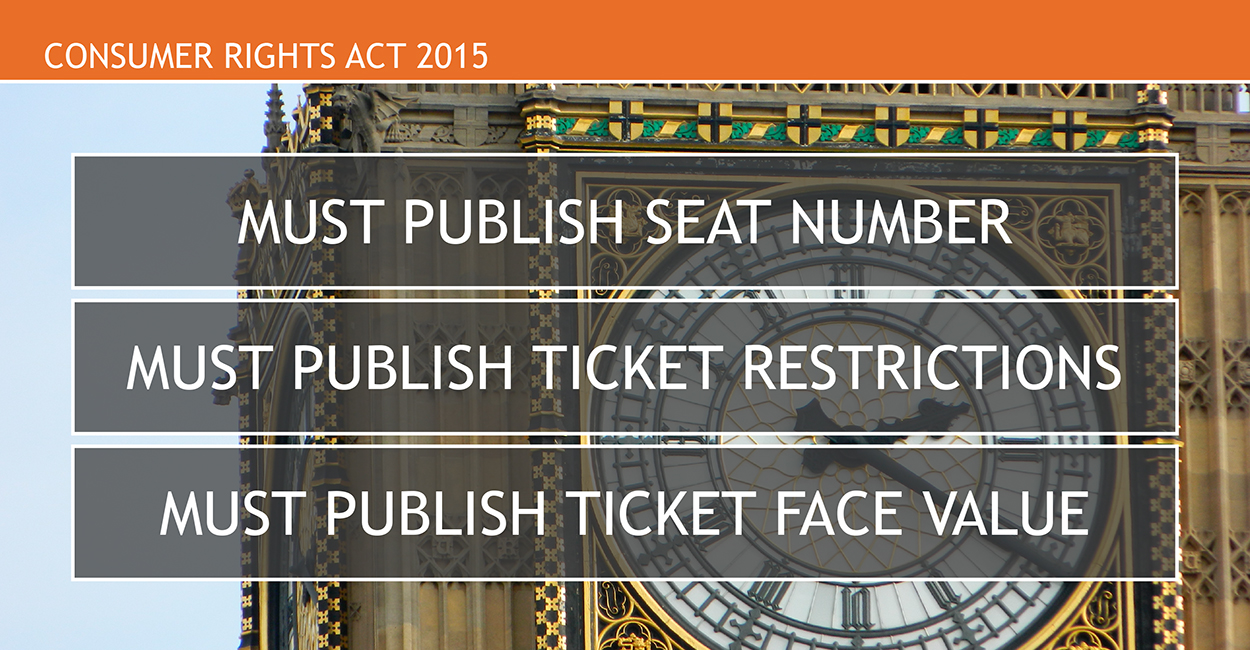

Two of those MPs – Mike Weatherley on the Conservative side and Sharon Hodgson on the Labour side – formed an all party parliamentary group to bring those concerned MPs together. They then used government plans to pass new consumer rights legislation as an opportunity to sneak some light regulation of ticket touting into the law.

Although Weatherley and Hodgson didn’t get everything then wanted into the 2015 Consumer Rights Act, touts were now obliged to publish seat numbers, restrictions and the face value of any tickets they were reselling. But perhaps more importantly, the Act also instigated a review of secondary ticketing led by Professor Michael Waterson, which ensured that the issue remained on the political agenda. And as the years passed the mood changed in Westminster and Whitehall, with more politicians supporting more regulation.

That, in turn, provided new impetus for anti-touting campaigners within the music community, many of whom had become disheartened by the general lack of political support in the early days of secondary ticketing. A number of those people – especially among the management community – launched the FanFair campaign, creating a louder more coordinated voice calling for more regulation of online touting.

06. The Waterson Report resulted in the law being better enforced

Although the Waterson Report did not go as far as some campaigners would have liked, it did two important things. It confirmed that the secondary ticketing platforms as well as the touts themselves were responsible for ensuring regulations were adhered to. And it urged the government to provide funding to bodies like the Competition & Markets Authority and National Trading Standards to enforce the law.

The latter point was key. Even once the Consumer Rights Act was passed by Parliament, many touts and resale platforms did not comply with the new rules. Meanwhile legal experts pointed out that there were existing consumer rights laws that the resale sector was also ignoring. These and other subsequently passed laws would achieve little if nobody was actively enforcing them against ruling-breaking touts and platforms.

The Competition & Markets Authority decided to take on the latter. In late 2017, the CMA made a number of demands of the big four resale platforms then operating in the UK: Viagogo, eBay’s StubHub, and the Live Nation/Ticketmaster-owned Seatwave and Get Me In. These demands required all four sites to change their polices and amend their websites to fall in line with consumer rights law.

When Viagogo refused to voluntarily comply, the CMA took legal action, won a court order and ultimately began contempt of court proceedings against the Viagogo company and its senior management team. Once contempt proceedings were underway, Viagogo eventually agreed to change its policies and practices in line with the CMA’s demands.

Meanwhile National Trading Standards decided to take on individual resellers. Its investigation resulted in nine industrial-level touts being charged in October 2018. Two of those people were then found guilty of fraudulent trading in February 2020 and were sentenced for a total of six-and-a-half years in jail.

Of course, this action is no panacea and tickets continue to be touted for profit in the UK. However, the work of the CMA and NTS has reduced the number of players in the UK resale market; forced the remaining platforms to alter the way they list and promote tickets providing more transparency for customers; and created significant media coverage to educate consumers about the difference between primary and secondary ticketing.

Increased transparency on the resale platforms has also made it a little easier for promoters of in-demand shows to cancel touted tickets. The sharing of knowledge and experience via the FanFair initiative also helped with that process. As a result, a number of major league artists have pursued anti-touting strategies of this kind, which has had a financial impact on the touts and further educated the public about the risks of buying tickets from resale sites.

07. New regulation was introduced in multiple countries

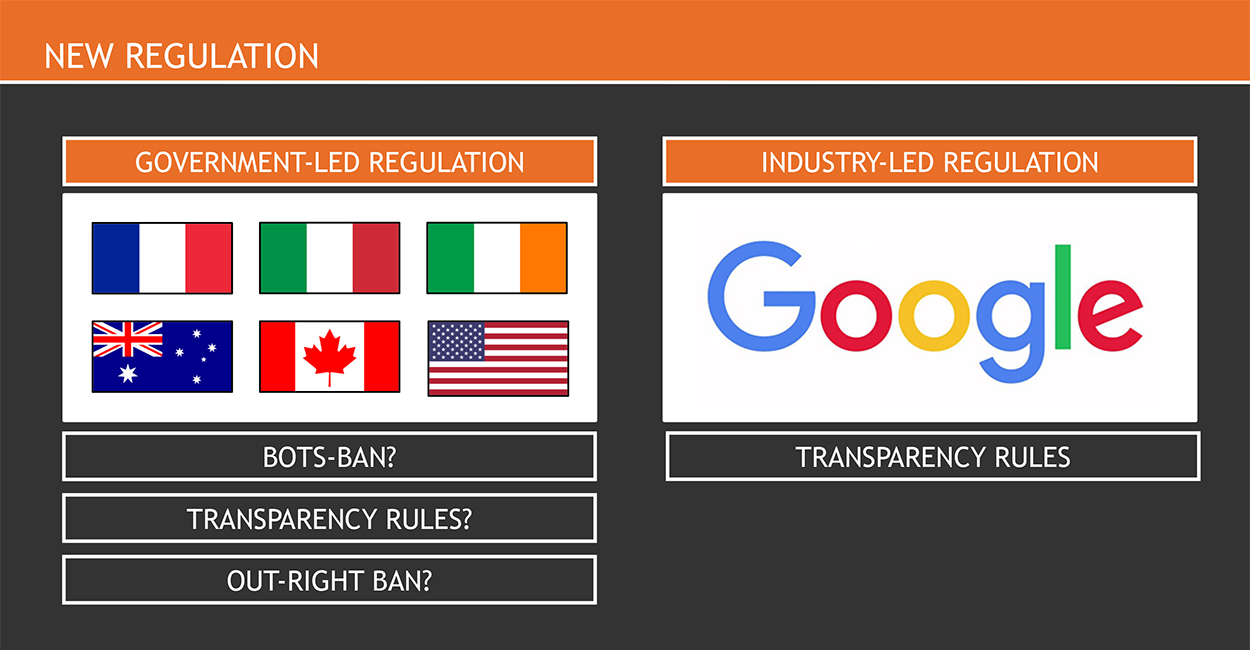

It wasn’t just in the UK that politicians became more willing to regulate secondary ticketing during the 2010s. New rules were passed in multiple countries.

A common starting point for regulation is the so called bots-ban. This is a rule that outlaws the use of bespoke software by the touts to buy up large quantities of tickets from the primary websites. The secondary ticketing firms have often supported this rule, arguably as a distraction tactic to push responsibility onto the touts themselves and to delay laws that have a more direct impact on the resale sites. But nevertheless, even in the US, where generally touting has been much less regulated, a bots-ban was passed at a federal level.

Beyond the bots-ban, some countries – like the UK – sought to force more transparency onto the platforms, educating consumers and making it easier for promoters to cancel touted tickets. Others went further, instigating outright bans on the resale of tickets for profit.

However, as in the UK, the key question in every country that has introduced new rules is always the same: who is going to enforce the law? In some countries – such as Australia and New Zealand – government agencies similar to the UK’s CMA and NTS have likewise taken responsibility for forcing touts and resale platforms to comply with the rules.

Beyond the law of the land, there was also a change to the laws of Google. Which was arguably more important, given resale sites have long employed often confusing advertising on search engines to reach consumers, many of whom assume the top link in a search list must be an official seller of tickets. Google also instigated a number of transparency rules for the secondary ticketing platforms and – although it hasn’t always enforced those rules effectively – some sites have been denied paid Google listings at various points.

08. Live Nation bailed on secondary ticketing – although not in the US

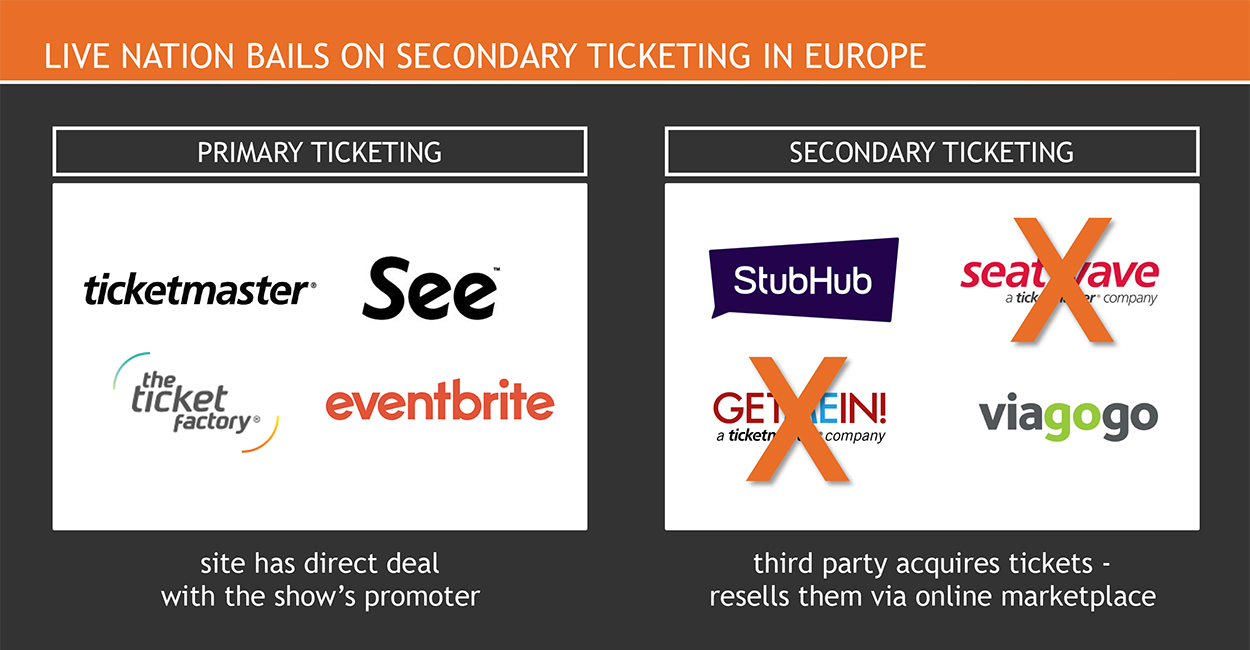

One of the big developments in the secondary ticketing story came in 2018 when Live Nation’s Ticketmaster announced it was closing its for-profit resale sites across Europe.

After Ticketmaster moved into the resale business in the 2000s, both it and parent company Live Nation had repeatedly defended secondary ticketing, even as an increasing number of the artists and promoters it worked with became vocal critics of the touts. However, confirming that the mood had shifted significantly across the political and music community in Europe in the preceding years, in August 2018 that position changed.

Ticketmaster UK said in a statement: “We’ve listened and we hear you: secondary sites just don’t cut it anymore and you’re tired of seeing others snap up tickets just to resell for a profit. All we want is you, the fan, to be able to safely buy tickets to the events you love”.

However, while Ticketmaster-owned Seatwave and Get Me In closed in Europe, the Live Nation ticketing firm continued to operate its resale platforms in the US, where touting has not generally been as controversial (although it does vary from state to state). That said, there have since been some media exposés on Ticketmaster’s secondary ticketing business in the US and law-makers in Washington are becoming more vocal on this issue.

Meanwhile, back in Europe, many other major players in live music – including Live Nation’s big rival AEG – also ended the official partnerships they had previously had with the secondary ticketing platforms, formally shifting to the anti-touting side of the debate.

09. Face-value resale became a much bigger thing

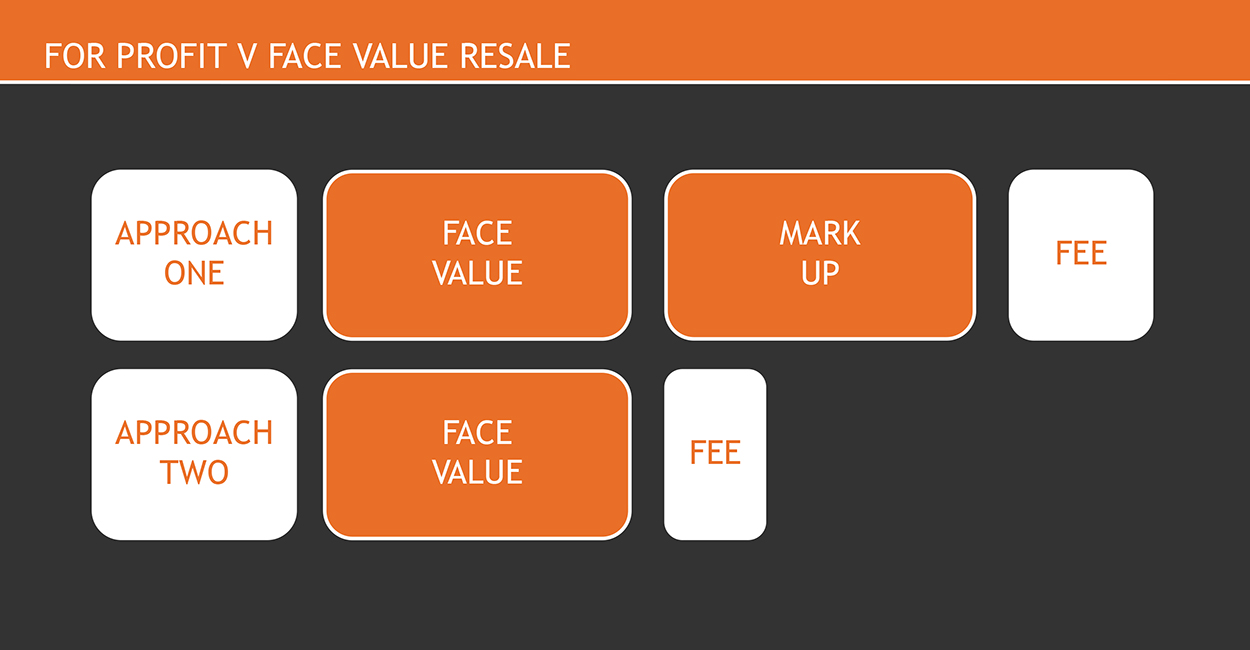

A common defence presented by supporters of touting relates to the fact most promoters have a strict no refunds policy on their tickets. Touts argue that it’s unfair to stop fans who buy a ticket intending to attend a show – but who then, for some reason, cannot – from selling that ticket on so that they can get their money back. Most people – including those who have campaigned against online touting – would agree with that argument.

In the early days many of the secondary ticketing websites defended themselves by claiming that the vast majority of sellers on their platforms were genuine fans in that exact situation. Anti-touting campaigners disputed that claim. While it may be true that most resellers on the resale platforms are fans of that kind, the vast majority of the tickets resold actually come from a small community of industrial-level touts. And without those industrial-level touts, the resale platforms would not have enough transactions to be commercially viable.

A key development that countered this defence of the resale platforms was the launch of websites that only allow tickets to be resold at face value – possibly with a nominal admin fee for the website operator. These websites have often been endorsed by those who oppose for-profit touting, with many artists and promoters officially sanctioning one specific face-value resale service for those fans no longer able to attend a show.

In more recent years many of the primary ticketing companies have started adding face-value resale functionality, including Live Nation’s Ticketmaster after it shut-down Seatwave and Get Me In, and AEG’s AXS after its owner ended its partnership with StubHub.

10. The spotlight may now fall onto primary ticketing

It would be wrong to say that the campaign against for-profit online ticket touting is at an end. New regulations are not always enforced. Even where they are, they often don’t stop for-profit resale entirely. And not every country where touting is significant has yet sought to regulate the touts and the platforms they utilise.

However, in multiple countries there is now more transparency, making it easier for consumers to spot the official from the unofficial sellers, and for promoters to cancel touted tickets for in-demand shows. Nevertheless, the debate over secondary ticketing continues.

That said, in the coming years the debate could shift over to primary ticketing. At various points the resale sites and the touts have tried to counter criticism of their practices by pointing out issues with the way tickets are allocated and sold by promoters and the primary ticketing agents they work with. And as campaigners have called for more transparency in the secondary market, the resale sites and the touts have often argued that the primary market lacks transparency too. And they generally have a point.

Therefore, we could start to see the spotlight increasingly fall on practices in the primary ticketing market. Indeed, in the US, recent discussions in Washington about regulating ticket touts have been part of a wider debate about the entire ticketing sector. If new laws are ultimately passed at a federal level in the US, it seems likely they will cover both primary and secondary sites. Which could kickstart a debate on the former in other countries too.