This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

CMU:DIY Guides Streaming Business Library

The Streaming Debate Explained

By Chris Cooke | Last Updated: January 2023

There have been lots of debates about the economics of music streaming of late – here we explain what that’s all about in five easy steps.

You can also download the slides that accompany the lecture version of this guide and buy the ‘Dissecting The Digital Dollar’ book published by CMU and the UK’s Music Managers Forum. Plus check out more music streaming resources available elsewhere in the CMU library.

#01: Subscription streaming is a revenue share based on consumption share business.

Most music streaming services – like Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music, Deezer and so on – operate a similar business model, which is a revenue share based on consumption share model.

Each service negotiates licensing deals with record labels, music distributors, music publishers and collecting societies.

Under those deals, a portion of the service’s total revenues each month is allocated to each track in its catalogue – based on what music has been streamed – and then a portion of that allocation is shared with the licensing partners that provided and licensed the track.

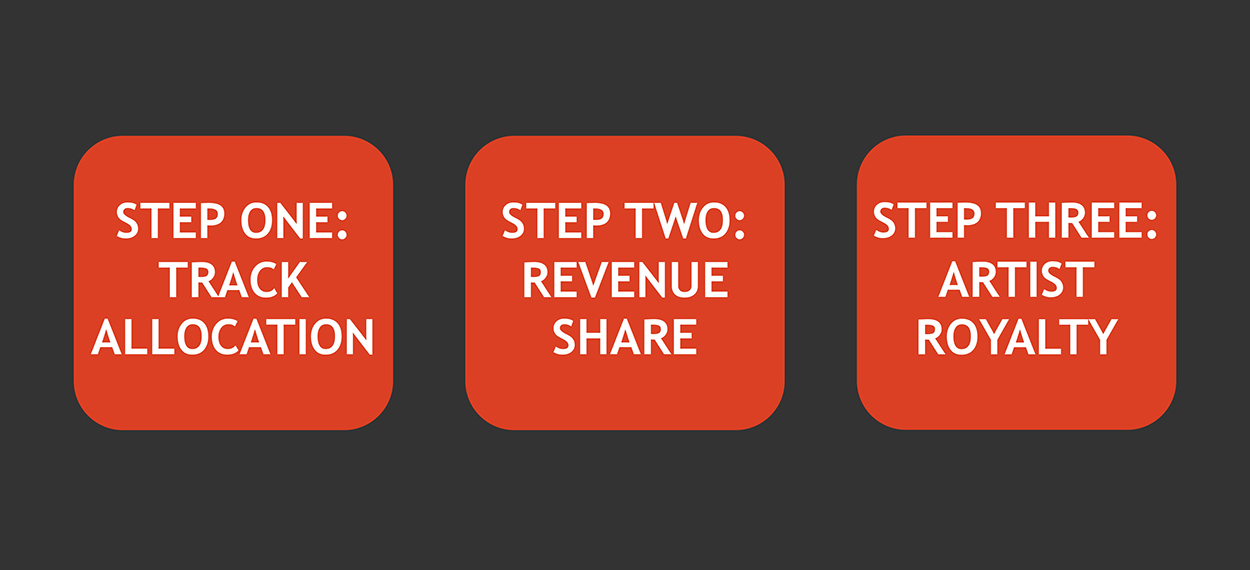

So, from an artist perspective, there is a three-step process to getting paid…

First, track allocation. Each track that has been streamed is allocated a share of that month’s total revenues based on what percentage of all the streams delivered by the service that month it accounted for.

So, for example, if one track accounts for 0.01% of all the streams delivered, it will be allocated 0.01% of the money.

Second, revenue share. Whatever money has been allocated to any one track is then shared with whichever label or distributor provided and licensed the recording, and whichever publisher or society controls the copyright in the song contained within the recording.

Every deal is different, but usually 50-55% of the track allocation is paid to the label or distributor, while 10-15% is paid to the publisher or society.

Third, artist royalty. The label or distributor will share what it receives with the artist, and the publisher or society will share what it receives with the songwriter. What cut of the money is paid to the artist and writer depends entirely on the deals they have done with their label, distributor and/or publisher, and/or any one collecting society’s distribution rules.

When it comes to artists and recordings, the artist could be getting anything from a few percent to 100% of the money.

If the artist releases their recordings via their own label using a DIY distributor like TuneCore or Distrokid to which they pay an upfront distribution fee, then they might get 100% of the money.

If the artist has signed a conventional record deal with a record label in recent years they will likely get 20-25% of the money (although it could be up to 50%, especially if it’s a smaller indie label). If they signed a deal with a label 50 years ago, they might only be getting a few percent.

#02: There has been a big debate over the way streaming works – and especially how the money is shared.

As it is labels, distributors, publishers and societies that negotiate the licensing deals with the services, artists and songwriters aren’t usually actively involved in developing digital music business models.

As a result, artists and songwriters – and their managers and other advisors – have raised a number of issues with the main streaming business model over the years. Of particular concern is how streaming income is shared out across the music community – what we call the ‘digital pie debate’.

This particular debate increased in volume during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most music industry revenue streams were negatively impacted by the pandemic, with live revenues basically stopping entirely. However, subscription streaming – and especially premium subscription streaming – wasn’t affected by the COVID lockdowns and continued to grow.

As a result, those artists who make only nominal sums from streaming started to more publicly scrutinise the streaming business model, with many arguing that that model – and the way the digital pie is currently sliced and the money shared – is unfair and should be changed.

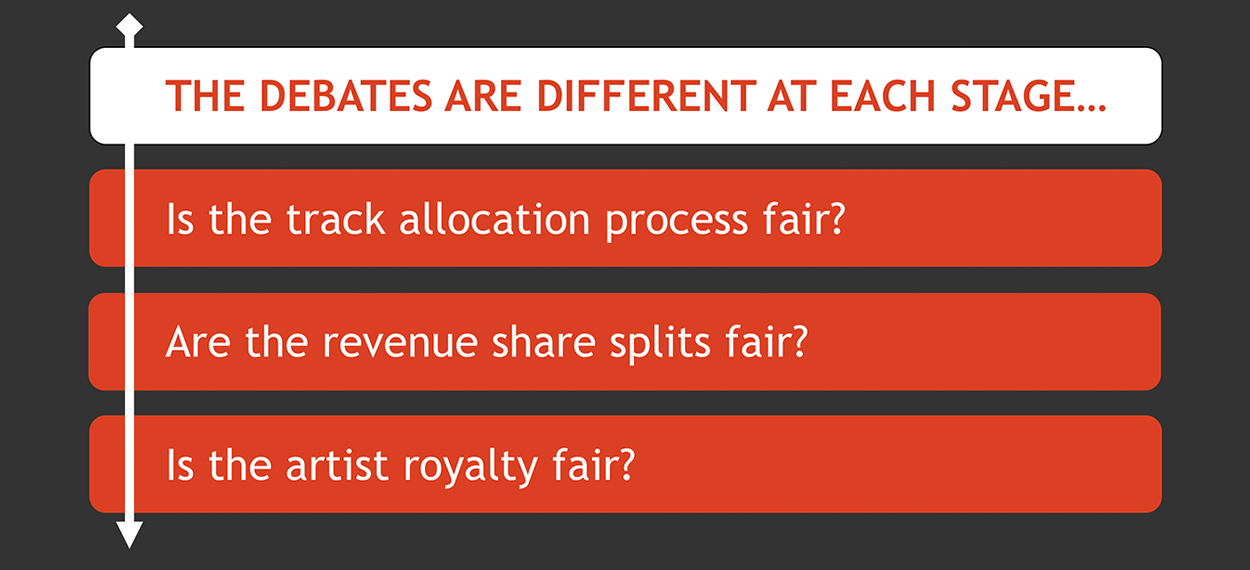

Issues have been raised with each of the three steps that we outlined above.

First, track allocation. Currently all the money a streaming service makes from selling subscriptions in any one market is pooled and allocated to each track based on what percentage of total listening that track accounted for.

But some people argue that, instead of that approach, each individual subscriber’s payment should be specifically allocated to the music – recordings and songs – that person has listened to. This alternative method is usually referred to as the ‘user-centric’ approach.

Because some subscribers listen to lots of music each month and some subscribers relatively little, under the current system some of the subscription fees paid by the latter group is allocated to tracks listened to by the former group. Under a user-centric approach that wouldn’t happen.

Opinion is divided on what impact adopting a user-centric approach would have on how much money each track is allocated, though some argue that less mainstream artists and releases would see a higher allocation, while the biggest acts and hits would get less.

Other proposals have also been made regarding track allocation, and that includes what is known as the ‘artist growth’ approach.

This works a bit like a bulk-buy discount, so that slightly less is allocated to the most-streamed tracks – ie the average amount per play is reduced – and that money is then reallocated to some of the less streamed tracks instead.

Some also argue that another current rule – that a single play is counted at 30 seconds – is unfair on genres such as classical that generally make longer tracks, and that additional plays should therefore be counted on a longer track, maybe for every five minutes that it is played for.

Second, revenue share. Many songwriters and music publishers argue that the current split between the recording and the song, so that 50-55% of revenue goes to the recording and only 10-15% to the song, is unfair.

With physical discs, the song actually got an even smaller share – with the shift to downloads and then to streams, the song’s share has slowly increased.

But some writers and publishers argue that it hasn’t increased enough, and that the song should get a bigger cut, and either the labels or the services (or both) should get less to allow that to happen.

Third, artist royalty. It is generally artists who signed conventional record deals who have grievances here – as songwriters usually see the majority of any income under a publishing deal, and those artists working with distributors are likely getting the majority too.

Most aggrieved are those artists locked into older record deals that often pay a lower – and sometimes much lower – artist royalty than new record deals.

Traditionally it was common for artists to sign life-of-copyright record deals, which means the label owns any recordings released under the deal for as long as they are in copyright, so 70 years after release in Europe. Which means artists stuck in those unfavourable old deals can’t do anything about it.

Some labels actually pay a modern royalty rate on streaming income to all artists in their catalogues, oblivious of whatever any old deals may say.

However, not all labels take that approach, so some artists whose old deals pay a 10% royalty on physical sales are still getting just 10% of any streaming revenue their recordings generate.

Under the current model, session musicians don’t receive any cut of streaming income, they being paid one-off upfront fees by frontline artists or record labels for each recording session.

That is also the case with physical discs – although session musicians do share in the record industry’s broadcast and public performance income because of the principle of performer equitable remuneration.

#03: Various ways for forcing a re-slicing of the digital pie have been proposed.

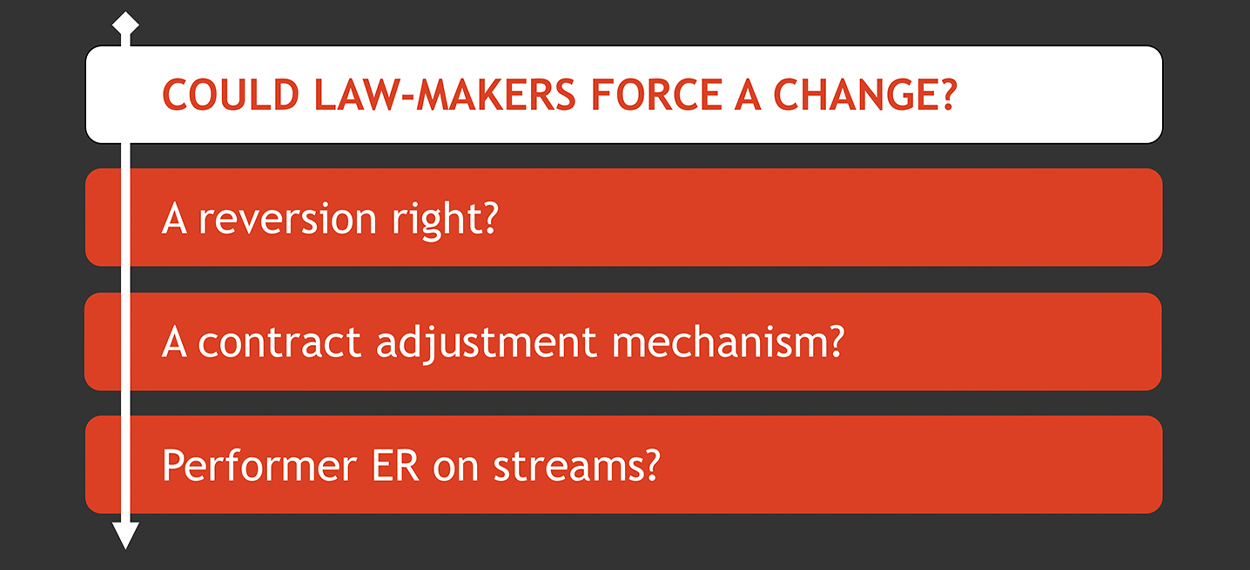

If many artists and songwriters feel the current streaming business model is unfair, how can they get things changed? Could copyright law be rewritten to address some or all of the grievances?

At least three copyright law reforms have been proposed. These are mainly focused on addressing the issues around the artist royalty, especially for those artists locked into older record deals that pay a lower rate.

One proposal is that a reversion right be introduced into copyright law. This would allow artists to terminate old record deals after a period of time and reclaim the rights in any recordings released under those deals.

A reversion right after 35 years already exists under US copyright law, although – for technical reasons – there remains a debate over whether that right actually applies to record contracts.

If such a right was introduced elsewhere, the big question is whether it would apply to all existing deals or only to deals signed after the new right was introduced. The current American reversion right was not applied retrospectively when it was added to US copyright law in the 1970s.

Life-of-copyright record deals are actually becoming less common. With new deals, ownership of any recordings may transfer to the artist after a period of time anyway, making any new reversion right irrelevant.

Another proposal is a contract adjustment right. This would force labels to renegotiate old record deals after a period of time, allowing an artist to – among other things – push for a modern artist royalty.

Quite how such a right would actually work – and what would happen if the artist and label could not agree new terms – isn’t clear.

A final proposal is that the aforementioned principle of performer equitable remuneration be extended to streaming.

This would mean that at least some of the artist’s share of streaming income would flow directly to each artist via the collective licensing system, with both frontline artists and session musicians getting a cut of that money at industry standard rates, oblivious of any contracts they’d signed.

Quite how this would work is also unclear. If the same system as applies to broadcast and public performance income in the UK was adopted, 50% of any income allocated to a recording would flow directly to artists via their collecting societies, of which up to a third would go to session musicians.

Though it’s unlikely that system would be adopted. In the small number of countries where ER already applies to streams, a different system is used.

As an alternative to those three copyright reforms, some people have proposed that record labels sign up to a voluntary code which would see them commit to pay a minimum artist royalty rate across their catalogues, even when they are not obliged to do so by any one artist contract.

That voluntary code may also include some commitments to share some streaming income with session musicians.

As for the issues around track allocation and revenue share, it’s not entirely clear how copyright law could intervene.

In the US, where a so called ‘compulsory licence’ applies to streaming on the songs side, the revenue share enjoyed by the song rights has been increased in recent years. Although similar increases have actually been achieved in other countries through commercial deal-making, and generally the music industry does not like compulsory licences.

Some songwriters argue that the major music rights companies – so Universal Music, Sony Music and Warner Music – being major players in both recordings and songs has skewed things to the disadvantage of the song.

That’s because under record deals the label often gets to keep the majority of the money, whereas under publishing deals the writer gets most of the money, so the majors arguably have an interest in more streaming revenue flowing through their respective recording businesses.

It should be noted that the majors strongly deny that their recording divisions have any influence over the deals done by their publishing divisions.

Some songwriters have campaigned for competition regulators to investigate their claims regarding the majors skewing things in this domain – though the UK regulator undertook a market study and concluded that there was no evidence of anti-competitive conduct in the digital music sector.

#04: There are various issues with the streaming business beyond the digital pie.

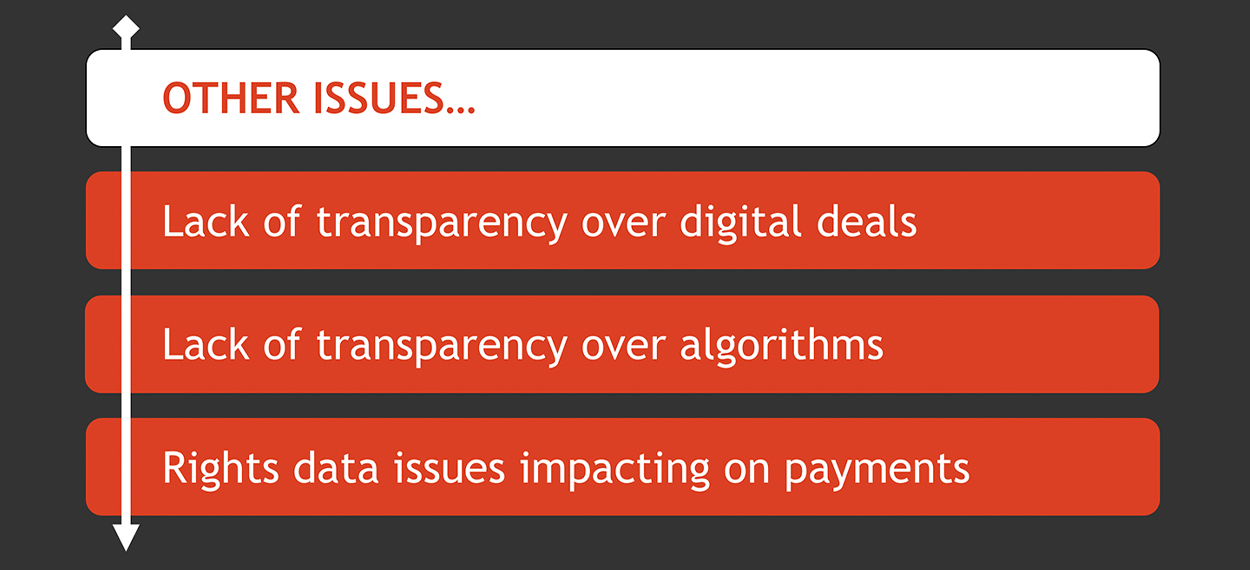

It’s not just the digital pie debate that has been in the spotlight – other issues have been raised too, in particular transparency and data.

Many artists, songwriters and artist managers have raised the issue of transparency – or, rather, the lack of transparency regarding how digital music deals work and how streaming income is processed and paid out.

Remember, artists, writers and managers are not generally involved in the negotiation of the digital deals, and those deals are usually secret and subject to non-disclosure agreements (aka NDAs).

In the early days of streaming, the services, labels, distributors, publishers and societies didn’t really communicate to artists, writers and managers how the streaming deals were structured and how everyone got paid.

This resulted in initiatives like ‘Dissecting The Digital Dollar’, where the UK’s Music Managers Forum worked with CMU Insights to figure it all out and then communicate key information to the management community.

In more recent years, some services, labels, distributors, publishers and societies have got better at passing information down to artists, songwriters and managers, although many questions about digital deals and royalties often remain unanswered.

Certainly music-makers would like those who negotiate the digital deals to be much more proactive in explaining to everyone else how things work.

Another area where there has been an increasing call for more transparency relates to how the streaming services recommend and push music to subscribers – so how the playlisting systems and algorithms employed by each streaming service work.

In this domain not only have artists, songwriters and managers called for more clarity, but we’ve had similar demands from some labels, distributors, publishers and societies as well.

One of the other big issues in streaming relates to music rights data – the data that identifies each recording and song, who controls the copyrights in each track, and what artists and songwriters need to be credited and paid.

Issues around rights data create complexities and inefficiencies in the way song rights are licensed and song royalties are paid. The MMF’s Song Royalties Guide outlines these issues while the MMF’s Song Royalties Manifesto proposes some solutions.

#05: In the UK the government is currently leading various initiatives looking into ways to evolve the streaming business.

Campaigning by artist and songwriter groups during the pandemic led to the Digital, Culture, Media & Sport Select Committee in the UK Parliament undertaking a big inquiry into the economics of music streaming.

At the end of that inquiry the MPs on the committee called for a “complete reset” of the streaming business, making many proposals for reform, including all three of the copyright law reforms outlined above.

Parliamentary select committees have more influence than power. Select committee member Kevin Brennan MP did actually put forward a so called private members bill in Parliament in 2021, among other things proposing those three changes to copyright law. However, bills of that kind don’t generally go through without proactive support from government.

In its response to the committee’s report, the UK government said that it recognised the legitimate issues that had been raised by music-makers, but would prefer a voluntary industry-led solution to copyright reform.

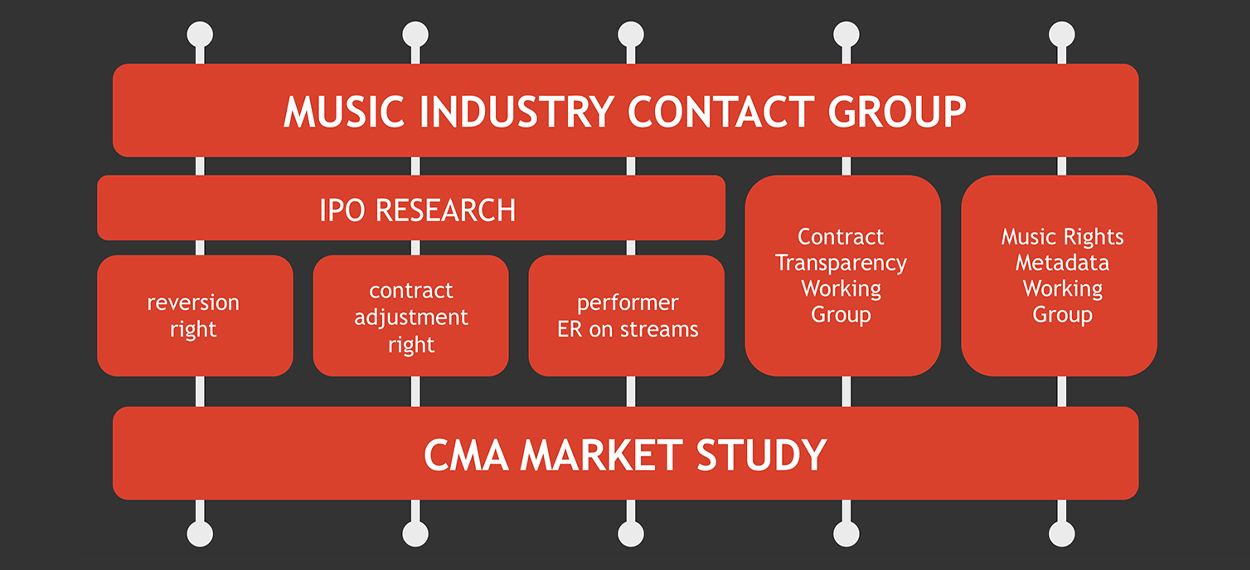

As a result, the government’s Intellectual Property Office instigated various research projects and working groups to consider the issues and possible solutions, with three main strands of work: music-maker remuneration, transparency and data.

Concurrent to that, the UK’s competition regulator – the Competition & Markets Authority – undertook its aforementioned market study.

In a subsequent report, the CMA also recognised the legitimate issues raised by music-makers, but said those issues were not the result of anti-competitive behaviour, so it couldn’t intervene. Instead, it said, the IPO instigated work should identify and implement solutions.

All of this IPO instigated work is very much ongoing as of January 2023. You can track CMU’s coverage of the economics of music streaming inquiry and resulting projects on this CMU timeline here.